This post may contain affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something we may earn a commission. Thanks.

For a passive source of food, your food forest garden must have self-made soil fertility built into its design. Various modes of general fertilizers are naturally produced from every forest.

Food forests need fertilizer. Fertility is vital for all plants to grow and comes from natural substances being added to the soil. Without a consistent source of material to build soil, growth will begin to decline. Fruiting plants that get heavily harvested rely on fertile soil to regenerate nutritious fruits.

If you don’t want to be the one to make, transport, and add fertilizer; build this function into your food forest system.

Our custom food forests can mimic most fertility-building traits from natural settings and become predominantly self-fertile too.

The strategy is to design your forest garden as a community, so it can fertilize itself with minimal supervision.

Who needs to go anywhere when all you need is where you are? A philosophy of every self-sufficient forest.

Confusion around fertilizer

Compost and mulch are often umbrellaed by the general term fertilizer because fertilizer is typically used to describe any substance that feeds soil or plants. Everyone defines fertilizer differently because there is a general term and a specific term.

The general and specific regard of the word fertilizer is often used as if they’re the same, but they are not.

In general, all plants (including food forests) need fertilizer; a source of fertility.

Specifically speaking, food forests don’t need fertilizer if we are referring to a processed extraction of readily available nutrients for plants.

Very significant distinctions.

So by general fertilizer, if we mean compost and mulch, your food forest does need a consistent supply of mulch and would benefit from compost in its early stages.

If you want to get specific about fertilizer, see: Mulch vs Compost vs Fertilizer (When to Use What). In regard to the specified definitions (rather than the general term) outlined in that article; food forests do not require a quick feed.

Quick-feeding organic fertilizers can be beneficial in numerous circumstances but are very rarely (if ever) required for a food forest.

A forest garden should never be given synthetic chemical fertilizers. As tempting as they are to quickly buy one of the shelves of a local store, synthetic fertilizers disrupt vital functions in soil ecosystems.

Synthetic fertilizers are designed to be perpetual inputs. Gardens using synthesized chemicals will rely on those chemicals to be applied on a regular basis.

What it means to sustain fertility in a food forest

A forest garden is meant to be self-reliant on pre-existing natural systems and upfront invested inputs.

Buying plants, soil, or mulch to set up your forest garden is to invest in enough biological capital that can be put together for sustainable use. After you acquire a reasonable baseline of resources, your goal is to grow and build these assets on-site with closed-loop systems.

If your site doesn’t require any vital ground preparation, the only imports you should need are a desired inventory of plants and seeds, and an upfront load of compost and mulch to get young plants established.

How you tend the plants from that point should result in spreading, propagating, and soil building. Giving back, not extracting.

New plants and seeds can be collected over time as you find what you want and discover new species. But you’ll want to avoid buying a lavender shrub, harvesting the whole thing till it’s dead, and buying a new one. That is unsustainable.

Instead, you want to give that lavender time to establish, harvest small amounts with proper pruning, and propagate it to make more lavender plants as projected necessary.

This same concept applies to your soil fertility. Part of a functioning forest garden is to accept death as not a loss but an opportunity for growth. We will talk more extensively about actual examples of built-in fertility below.

We are all responsible for Sustaining Biological Capital. As cited, you can see the forestry industry faces this issue as much as the food industry does. It’s a whole lot easier to control our own actions than it is to control others’ actions; so if we can provide much of our own food in a site-sustainable way then our actions produce biological profit rather than biological cost.

Semi-passive biological profit means money and time savings for you (and everyone else)!

All possible forms of fertility production should be able to come from the capital on the site.

Not all sites, especially space-limited sites, will be able to maintain all aspects of a forest garden without importation. For example, mushroom logs or woodchip beds will need out-sourced wood unless you own a hardwood-land property.

But alternatives and solutions can exist—straw mushroom beds are an option, and you don’t need too much space to grow a little patch of rye annually to maintain a small mushroom bed.

Fertilizer, meaning general fertility, in a food forest essentially refers to soil building with excess plant material and wildlife inclusion.

| Fertilizer Types | Should You Use it in a Food Forest? | How is it Locally Sustained? |

| Wood mulch | Yes! Wood chips mimic deadfall in a forest; downed trees or limbs. | Pruning branches or cutting pioneers at maturity. Lay them whole or chip them. |

| Leaves | Yes! Leaves fall in every deciduous forest. | Planting heavy-leaved deciduous trees. |

| Straw mulch | Yes! Be cautious & source uncontaminated straw, or grow it yourself. | Not sustained by the food forest, but by an open meadow. |

| Wildlife manure | Yes! Invite diversity into your food forest with habitat opportunities. | Simply by having an inviting food forest! More info is below in the post. |

| Livestock manure | Yes! Aged manure is a voluminous soil builder. | Herbivorous animals can eat plenty from food forest production. |

| Plant tea | You absolutely can, but isn’t a required effort for success. | Foliage from the food forest is steeped into a tea and poured diluted around unestablished plants. |

| Synthetic fertilizers | Never use biologically-disrupting chemical creations | It isn’t created by your food forest, so can’t be locally sustained |

This article was originally published on foodforestliving.com. If it is now published on any other site, it was done without permission from the copyright owner.

Human interventions such as pruning, chipping, or shredding are simply to speed up the process to a result that a natural forest would eventually come to. It’s okay to intervene to build soil faster! Passive fertility is the reward after at least a decade (or so) of building a functioning system.

Ways to build fertility into your food forest design

Biological capital not only needs to be included in our food forests but with a plan to be used.

See: How to Grow a Food Forest for Free and Cheap

Dynamic accumulators for food forest fertility

What’s known is that dynamic accumulation (Phytoaccumulation) occurs in one way or another, more or less depending on the plant. It’s unknown if, how, and when plants, that accumulate elements, will release them to be available in the soil.

Regardless, it’s safe to assume that dynamic accumulators are good to have in our forest gardens. We know that nutrients are being accumulated at the least, and perhaps, very likely being released for use at a later date, maybe upon decomposition of said plants, for the rest of our forest garden to consume and recycle over time.

Comfrey is the most popular “dynamic accumulator” that has actually displayed great results for numerous food forests! Permaculture news posted about their results here.

We have the sterile blocking-14 comfrey, but no personal soil test to display personal results (or lack of) at this time. Comfrey can be harvested and dropped onto the soil in place or around other plants between 3-4 times per year once established.

If you want to know more about comfrey, this is the book to read!

Mexican sunflower, goatweed, and plants of the Asteraceae and Compositae families have been studied and used for phytoremediation. Here is a greater list of these.

Russian comfrey, amaranth, and water hyacinth have shown they contain various concentrations of NPK when made into teas (which would be considered a quick-feed organic fertilizer).

But this doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to make plant tea to feed your food forest. It just shows that these plants do uptake plenty of nutrients that are likely to (eventually) become available after decomposition through chopping and dropping the foliage or terminating completely.

With the logic that accumulated nutrients are to become available upon termination and decomposition of the plant—we’re planting a mix of perennial, biennial, and annual accumulator ‘suspects.’

This way, we have short-term and long-term sources of diverse nourishment. We will allow annuals and biennials to passively live out their lifespan and use perennials as a manual chop and drop.

Unless the annuals and biennials reseed themselves, perennials may be less work.

Nitrogen-fixers for food forest fertility

Nitrogen-fixers refer to plants that exchange carbon with microorganisms for nitrogen to facilitate the growth of the plant. This means they don’t need to be in nitrogen-rich conditions to obtain nitrogen for growth. Nodules of nitrogen are displayed in their root systems. These nodules are released upon decomposition and nitrogen becomes available in the soil.

A similar concept to dynamic accumulators, except, this is an emphasis on nitrogen nodules on the roots of certain plants. Nitrogen fixers display a physical characteristic that is identifiable, whereas dynamic accumulators do not.

A mix of long-term and short-term nitrogen fixers for your forest garden is a good idea.

Long-term nitrogen-fixing trees and shrubs include (but are not limited to): black locust, alder, sea buckthorn, goumi berry, and many, many more!

These plants would grow for 5-10 (or more) years, and later, can be chopped down and killed (with persistence!) so that the nitrogen in their vast root systems can be released into your garden.

Short-term nitrogen fixers can include annuals, biennials, and shorter-lived perennials. These plants would range from natural lifespans of 1-5 years. A few examples are lupins, clover, hairy vetch, beans, peanuts, ground nuts, and peas.

These plants are either going to be (1) killed prematurely in your climate after the season is over and give back 1 year’s worth of growth or (2) Live out their lives over their typical span and die off and give back naturally, hands-free.

Clover typically lives 3 seasons, lupins can live between 2-5 seasons. Beans and peas in our climate would only live for a single season.

Pioneer trees for food forest fertility

Nitrogen-fixing trees make good pioneers, but not all good pioneers fix nitrogen. Pioneer trees (and plants) are hardy to your given environment and can withstand growing alone without the support of other plant species.

Even if they don’t fix nitrogen; pioneer species will provide lots of leaf litter and protection from winds, and excessive sun, and improve the soil conditions with their vigorous roots.

To find out what your best pioneer species are do a search for “pioneer species for your location“

Go through the ideas listed and sift through the list to find what species will be most useful for you. Pioneers may seem useless (if they aren’t what you want) but many are extremely useful and provide a hospitable environment for the plants you do want.

In eastern Canada, for example, we could use the following as pioneers to create a livable environment out of barren areas or harsh conditions:

Birch (Betula pendula) – Edible for tea and medicinal uses, USDA zones 2-6, wildlife attraction, can grow in heavy clay or nutritionally poor sandy soil, prefers well-drained dry or moist soil, windbreak.

Black alder (Alnus glutinosa) – Fixes nitrogen, USDA zones 3-7, wildlife attraction, Can grow in heavy clay or nutritionally poor soils, Prefers moist or wet soil, medicinal uses, windbreak, quick establishment, lots of leaves, dies out if shaded by other trees species. Coppice for wood use.

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) – Extremely nutritious berries, a nitrogen fixer, thorny, USDA zones 3-7, also grows in a wide range of soils, prefers moist or wet soil, but can tolerate droughts, can’t grow in shade, medicinal, will die if shaded by other species.

Sumac (Rhus glabra) – Tropical-looking foliage (very gorgeous coloring in fall too!), edible, medicinal, USDA zones 3-9, grows in a range of soils, prefers well-drained dry or moist soil, windbreak, attracts wildlife, can’t grow in shade, coppice for wood use.

White willow (Salix alba) – Edible for tea, USDA zones 2-8, wildlife attraction, can grow in heavy clay soil, prefer moist or wet soil, can’t grow in shade, amazing mulch for plants, windbreak, dynamic accumulator.

Wildlife habitats for food forest fertility

Incorporating as many layers possible into your forest garden (7-9 layers) will increase the diversity of habitat available for various critters.

Various critters play significant roles between each other, the plants, and the soil of your forest garden. While many are a nuisance it usually means you need to invite more for balance!

Problems will always exist, and can only be swapped out for another. The more complex systems are; the stronger they become, so inviting new ‘problems’ is the key to building a resilient, fertile, and passive food forest.

More habitat-friendly spaces mean more opportunities for complexity to build. See this section for plenty of easy and free (or inexpensive) habitat ideas.

Chickens for food forest fertility

Now, chickens may be beside your food forest, not roaming about inside. But having them as part of your system is a no-brainer if you’ve planned for excessive plant production beyond your own needs.

Feeding chickens with plant material grown by your food forest will render you eggs to eat, and manure to apply on heavily harvested plants or areas.

Chickens are less passive than plants, but they diversify your soil amendment options while providing you with the extra benefit of more food (and soil).

A balance between plants and animals

A sustainable and predominantly passive food forest requires inclusion. Even if you’re thinking you don’t want any of the above pioneer species, dynamic accumulators, or nitrogen-fixers taking up precious space, or wildlife stealing berries.

If you plan to take fruit, tubers, greens, and seeds from your forest garden for eating; excessive plant material for soil regeneration is essential, and wildlife provides plenty of dispersed manure.

Excess for you, and excess for the forest; is abundance for everyone!

Hands-free for you, means hands-on for everyone else. Every harvest will need a form of on-site replenishment.

The above elements will ensure you have a variety of regeneration opportunities such as:

- Leaf litter

- Wood from pruning or coppicing

- Sacrificial dynamic accumulators and nitrogen-fixers for nutrient-rich foliage compost and in-ground root mass decomposition

- Diverse predatory insects

- Habitat opportunities and wildlife interest elements

- Food for chickens; for manure and eggs

- Compost-tea if you desire to make it, but is not required for food forest success

Putting limitations on imbalanced wildlife is not off the table! Plenty of beneficial wildlings can do their thing while deer stay on the outside.

See: The Best Fence to Keep Deer Out (Cheaper & Easier Too)

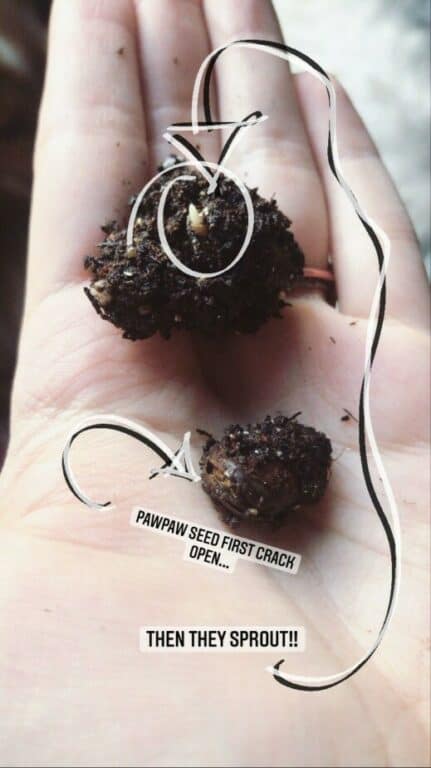

Plant propagation, natural re-seeding, and seed saving

Finally, to keep your fertile system going, you’ll want to expand or replace plants as they inevitably live their life cycle and die.

Many may naturally seed themselves, and end up where you do or don’t want them.

You can seed-save instead and decide where you want them.

Saving seeds can be tricky, but Remo Gentry has a thorough and straightforward guide to proper seed-saving. It includes harvesting, drying, techniques to speed up the process, proper storage, and more.

For expansion, propagation is easy for the most part and relatively quick. Sometimes, clippings of vigorous plants, like grapes, yield you so many propagations you don’t know what to do with them.

If you wanted to find something to do with them, David the Good offers his secrets in his book The Easy Way to Start a Home-Based Plant Nursery and Make Thousands in Your Spare Time. While I haven’t read it myself, I’ve heard great things about it and am considering it for myself soon!

If you like the idea of doubling your forest garden as a nursery side hustle, I recommend the book sooner than later—since he does teach you how to find your niche in the market. Understanding some preliminary information will allow you to set yourself up for success from the start.

I hope I’ve left you with plenty of resources to ensure you have a fertile food forest that doesn’t need fertilizer—especially from a store!

Please leave me a comment below!

Up Next:

Recent Posts

There’s no shortage of full-sun ground covers for zone 4 climates! Each plant in this list can withstand the frigid temperatures and also enjoy the hot sun in summer. Full sun means that a plant...

There's no shortage of full sun ground covers, not even in zone 3! Zone 3 climates offer hot but short-lived summers and very cold winters. So each plant in this list can withstand the frigid...