This post may contain affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something we may earn a commission. Thanks.

The wind is often the cause of a garden’s biggest threats. If you want a productive garden or food forest; a thoughtfully diverse shelterbelt can be more useful than a bland windbreak.

There is a difference between windbreaks and shelterbelts.

Windbreaks are usually considered a single structure or single row of plants in between the wind and your garden. For example, a simple row of Jerusalem artichokes, or a fence. Shelterbelts are a long stretch of multiple rows of hardy perennials that create a microclimate of protection for a resilient garden space.

Both are greatly useful! However, if you have the space for it, why not give yourself more than a windbreak?

A permaculture shelterbelt can be designed for both small and large spaces. Since forest gardens are such great investments, it’s important to protect them with thoughtful design.

Your shelterbelt can include edible, medicinal, and multi-purpose trees that can also house many of your food crops within the design. The rest of your food forest will thank you for such a stable and resilient space to grow.

In this post we’ll talk about how your shelterbelt will be plenty more useful than previously described, considerations for placement, how to determine wind direction, what to plant, plant spacing for layered food forests, and examples of different-sized windbreaks and shelterbelts!

The benefits of a shelterbelt

A well-done shelterbelt will extend you many benefits! For any situation, they create a microclimate that permits better conditions in your living space.

The microclimate created by a shelterbelt will help reduce your home energy costs, increase privacy, add to property value, save and produce water, minimize snow build-up, keep deer away from fruit trees, create a sanctuary for beneficial wildlife, and keep your forest garden a bit warmer in winter.

By reducing the winter wind chill in your forest garden; you may be able to get away with warmer-zone perennials.

For waterfronts; riparian shelterbelts are essential for protecting the water by controlling erosion and reducing waterfront winds from tunneling into your property.

If you live by a busy road; a shelterbelt protects your property from dust, noise, and road pollutants.

If you’d like a strong forest garden ecosystem; a diverse shelterbelt of all shapes and sizes can provide all sorts of habitat space for beneficial wildlife and medicinal food for you!

Consider the best place for the forest garden shelterbelt

When designing a shelterbelt; determine the function you’re after. Are you most concerned with the chilly winter wind, the summer storms, or both?

You can best protect your forest garden from weather and wildlife by planting it between your home and within the shelterbelt.

Questions you need to consider:

- Do you have space for a shelterbelt that will provide greater protection than pre-existing structures on your property?

- Do you only have space and budget for a small shelterbelt where perhaps your home would provide greater protection from wind? This will help you decide what side of the house to put your forest garden on in relation to the predominant direction of the concerning wind.

- Concerning wind would either be winter or summer: the two climatic extremes; which is more detrimental in your area?

- When will your trees be fruiting and where is the wind during that time?

You’ll generally always want to protect a forest garden from winter winds and blowing snow. In summer, wind protection is also important if your area has storms.

You can also consider the direction that wildlife is most likely to come from. A strategically planted shelterbelt is more likely to keep deer on the outside than your easy-to-walk-beside home.

One last thing you definitely need to consider is the shade your mature shelterbelt will cast.

How do you find the wind direction of a place?

To create a functional shelterbelt, you’ll need to know where the wind comes from in general. This depends on your general area in the world, nearby terrain, property landscape, and pre-existing structures.

Since these levels of consideration may exist for you, the best way to find the wind direction of your specific place or property is to observe and record clear patterns in each season. If you want your shelterbelt investment to be the most effective, it’s worth taking the time to monitor first and act second!

Sometimes the placement in a given layout is quite clear and you can go ahead with the project with good results. But all the considerations outlined might make you rethink the shape and design you choose!

The general area you live in will have predominant winds for each season as the pressures on earth fluctuate as our positioning and distance from the sun change.

The general wind direction will be what is as high as the sky. However, at ground level, the direction of the wind diverts slightly as it passes through your property if you live within hills or mountains. Few forces will obstruct wind direction in open fields.

Your property landscape might; passively allow the wind to hit your house and fly by, create a wind tunnel effect, or redirect the bulk of force and slow the wind that enters. With a shelterbelt, we aim to achieve the latter.

To quickly determine wind directions on your property:

For those who live by wide open fields, you can easily rely on free historical data from local weather networks or airports.

Anyone can benefit from using this method to confirm their observations!

For those in more complicated terrain; you can note the way tall grass tends to lean for predominant property wind direction in summer. For winter, you can count on the tallest banks of snow against the house or other structures to give away your predominant property wind-storm direction.

You can also observe the wind direction using any one of these methods:

- Look to a flag

- Look to a wind vane

- Look at the trees

- Observe the way tall grasses generally lean in summer; even on non-windy days.

- Drop a handful of dried leaves in fall

- Drop a handful of snow in winter

- Drop a feather in spring

- Stand and turn until the wind is in your face and record the direction you are facing

Plant spacing in layered food forest and wind shelterbelt

Your shelterbelt can be dense or spacious. You’ll want to go for something in between.

When winds go over mountains or hills, they blow back down where they can and this creates a wave. This wave pattern can continue even after the obstruction becomes clear.

If you plant your shelterbelt with too much density and block all the airflow; you’ll cause this effect; resulting in stronger down winds coming into what could be the protected zone. The more dense your shelter belt, the less protected space there will be.

Having air pass through your shelterbelt; softens the turbulent down-winds by taking up the space.

Airflow is also vital for preventing disease, exchanging gases, and allowing resistance to increase the stem strength of trees and shrubs.

Good airflow means you didn’t overcrowd your trees and shrubs. This will keep your shelterbelt performing and growing bigger for a longer time. Plus, it will be easier to maintain, weed, or plant something in between.

Finally, you also want to avoid major or imbalanced gaps that would create a wind tunnel effect.

If you end up with gaps from failed plantings or other reasons, supplement the space with Jerusalem artichokes.

If you accidentally plant too densely, you can prune your plants to promote at least some human-level airflow.

As a general rule, follow the spacing guidelines for the trees and shrubs you choose!

Example shelterbelts and windbreaks for inspiration

You can make a shelter belt with a diverse range of native species or with large hardy fruit and nut trees to be your windbreak. The first creates wild habitats that benefit the forest garden, and the second will provide protection for everything else while still giving you a fruit or nut yield.

For multiple reasons, If you have the space, I definitely recommend using native windbreak trees that are best for the job. When using food-producing plants as a windbreak, expect smaller yields because they won’t be thriving. Trees that aren’t thriving tend to be taken advantage of by pests and disease too! Not ideal for your goals.

A bonus is that most native wind-protecting trees have medicinal and edible uses too! Going the wild-habitat route benefits the bigger picture in the end for everyone.

Below are a few design examples to give you inspiration on how to create a suitable shelter belt for your budget and space.

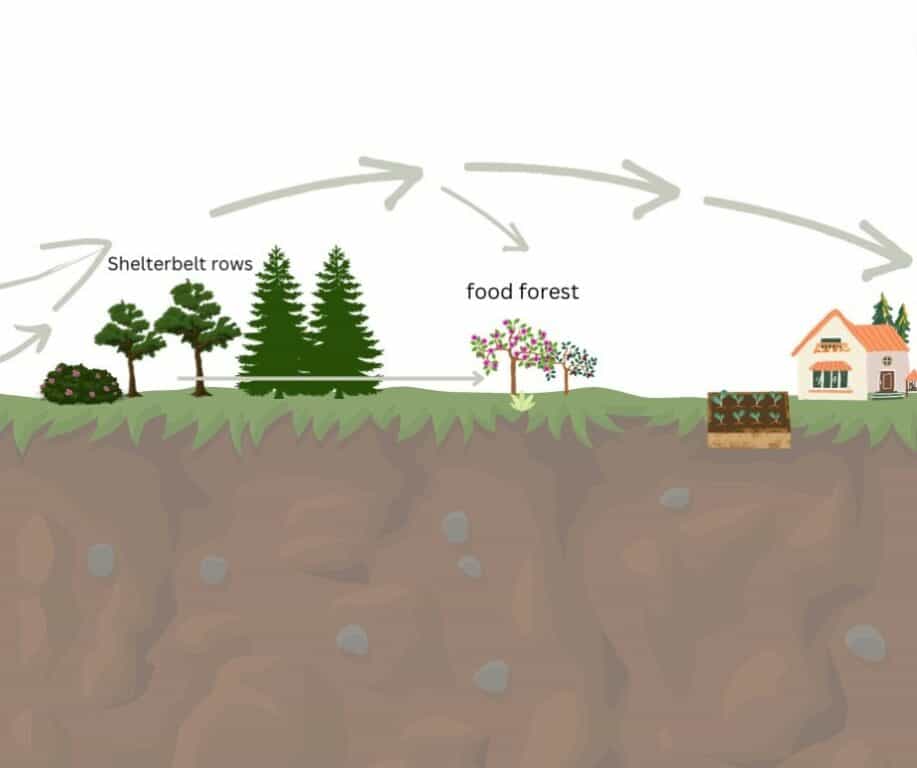

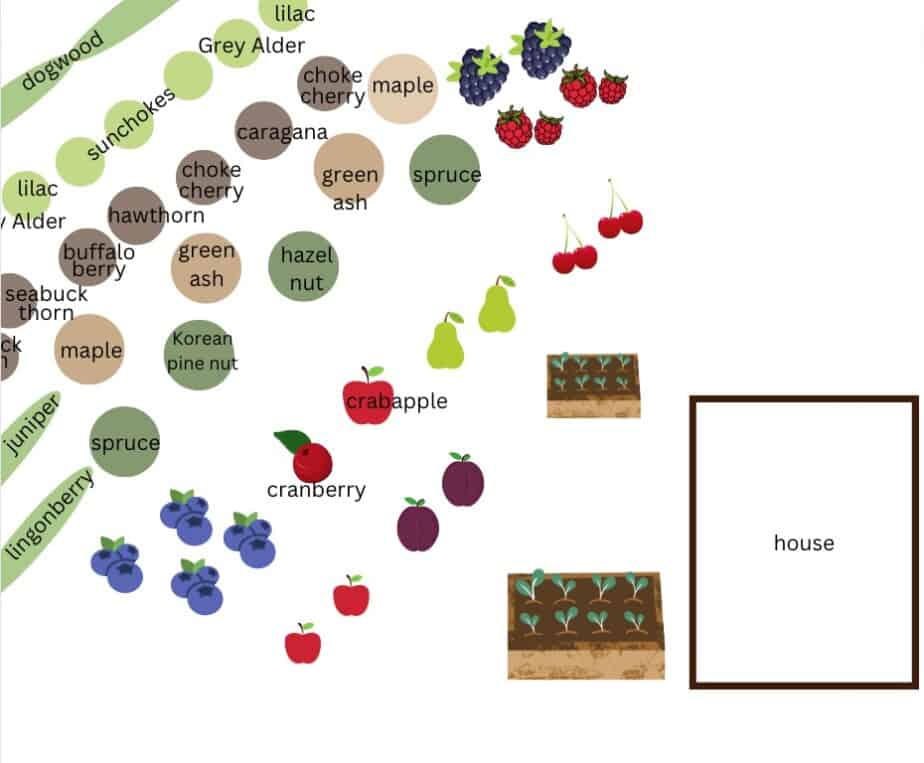

Example 1: Five-row windbreak/shelterbelt for a protected fruit-tree forest garden

- Your shelterbelt is made up of the hardiest, strongest, and most dense-growing forest garden trees and shrubs. Everything is spaced to allow airflow through the shelterbelt. The beneficial airflow coming through reduces the strength of downwind that would come from the top down into the protected area.

- The space between the shelterbelt keeps the snow away from the forest garden and allows more light to hit your fruit trees which may allow snow to melt quicker in spring.

- The gradual wind climb and width of the height allow for a long distance of protection.

Explanation of plant choices: Dogwoods grow prolifically and low to the ground creating a low-ground barrier for the wind to climb. A bit taller, we could put in a mix of food (sunchokes), flowers (lilacs), and nitrogen fixers (grey alders). In the 3rd row, the height increases once again: a mix of food, nitrogen, and bird habitat with trees and shrubs; seabuckthorn, buffaloberry, hawthorn, caragana, and chokecherry. The fourth row has more deciduous, long-standing trees, maples for food and leaf litter, and extreme climatic tolerance of green ash for nitrogen fixing and timber. Finally, in the 5th row, spruces for density and long lifespan, Korean pine nut for delicious nuts, wind resistance, bolete fungi, and height, and hazelnut for more food, longevity, and leaf litter. In the fruit tree area, place the blueberries, lingonberries, and cranberry in the more acidic soil environment with the spruce, pine, and juniper.

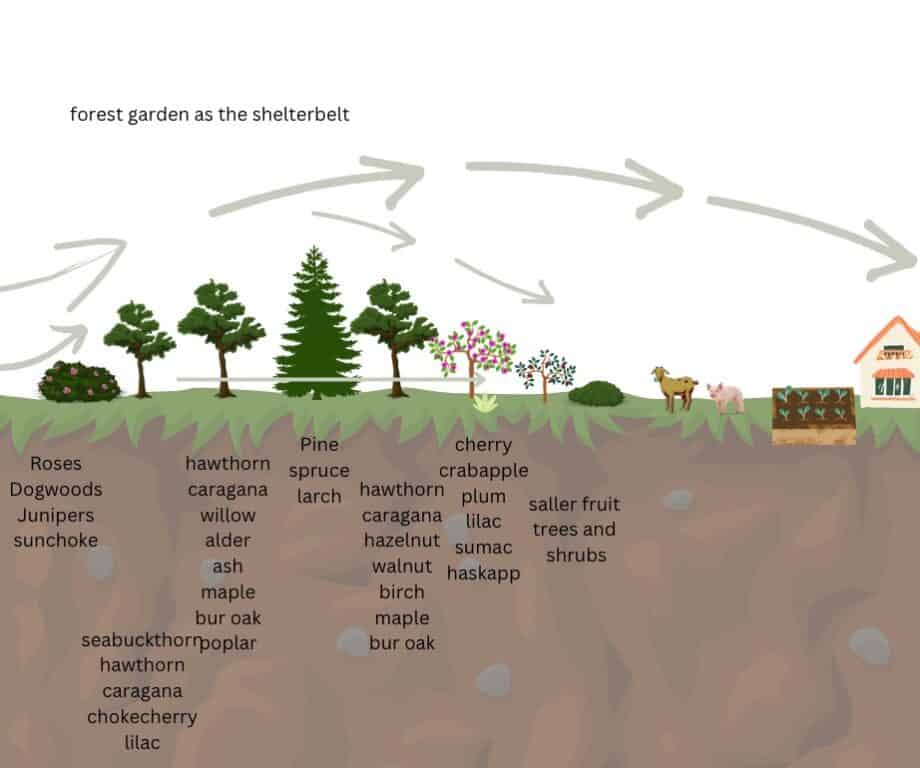

Example 2: Eight-row Forest garden as the whole property shelterbelt

- With this design, you may have more snow build-up around your edible plants as they are part of the overall property shelterbelt. The shaded environment caused by the rows of trees may make warming over spring take longer in the forest garden, but not the annuals by the house. Airflow through the design slows strong winds but is still abundant enough to minimize mildew, stagnant cold air, or frost.

- You’ll have more food, more resources, and a large forest ecosystem and microclimate that may cancel out the effects of the shade with strategically-pruned trees. It is likely to keep warm over winter and you may be able to get away with plants that don’t typically grow in your zone.

- The gradual wind climb and peak height allow for a long distance of protection.

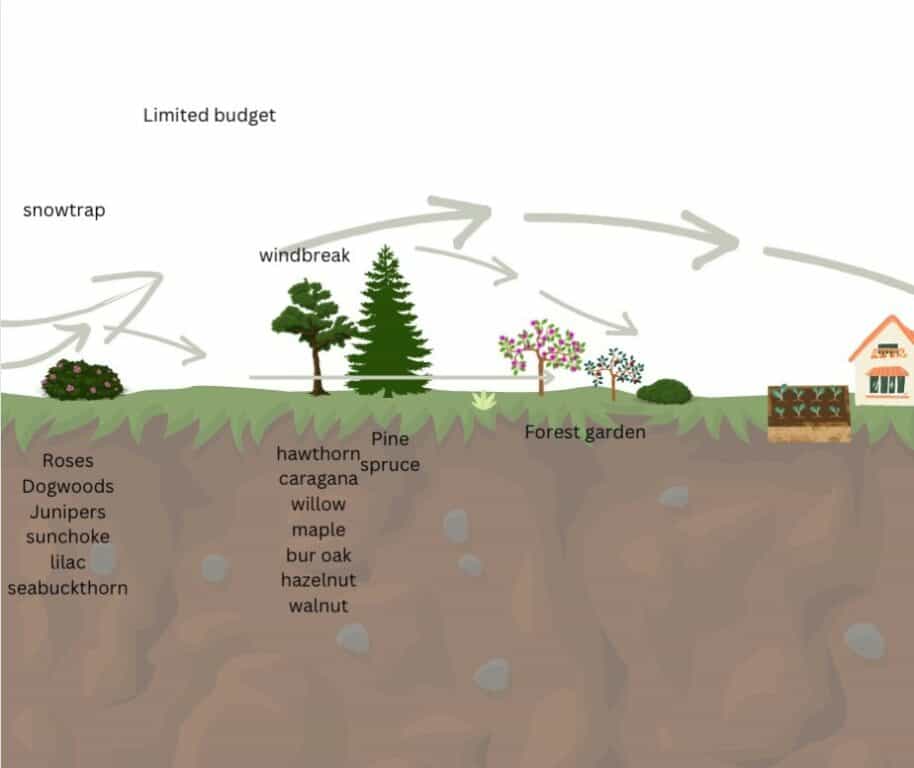

Example 3: Limited budget shelter for forest garden with a snow trap

- The snow trap will accumulate the most snow, and a secondary pile-up will happen at the two-row windbreak. Snow will be minimized in your forest garden and the sun will be abundant which could mean that spring may prop up quicker. However, less snow in winter means a thinner blanket from the chill so there is less of a microclimate effect over winter.

- The thinner shelterbelt/windbreak also means faster windspeeds inside the protected area but less turbulence from downwind.

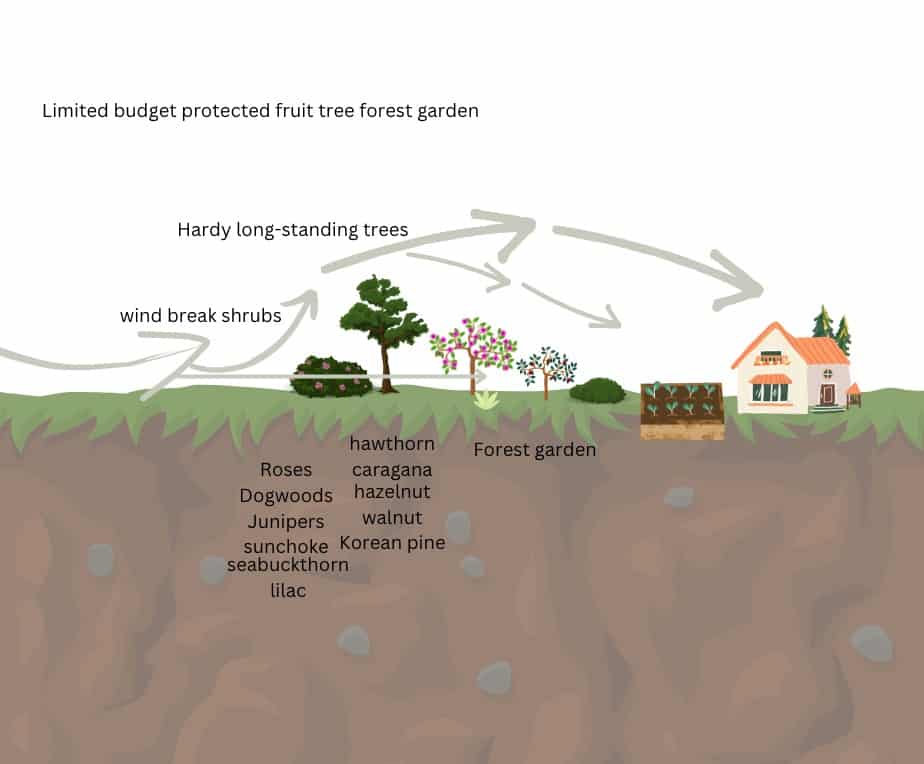

Example 4: Limited budget and space windbreak for forest garden

- Your forest garden is protected from the chilliest and strongest winds from the combination of a low and tall windbreak. The distance of protection is largely decreased with less height.

- The windspeed is reduced somewhat in the protected area but not nearly like in previous examples.

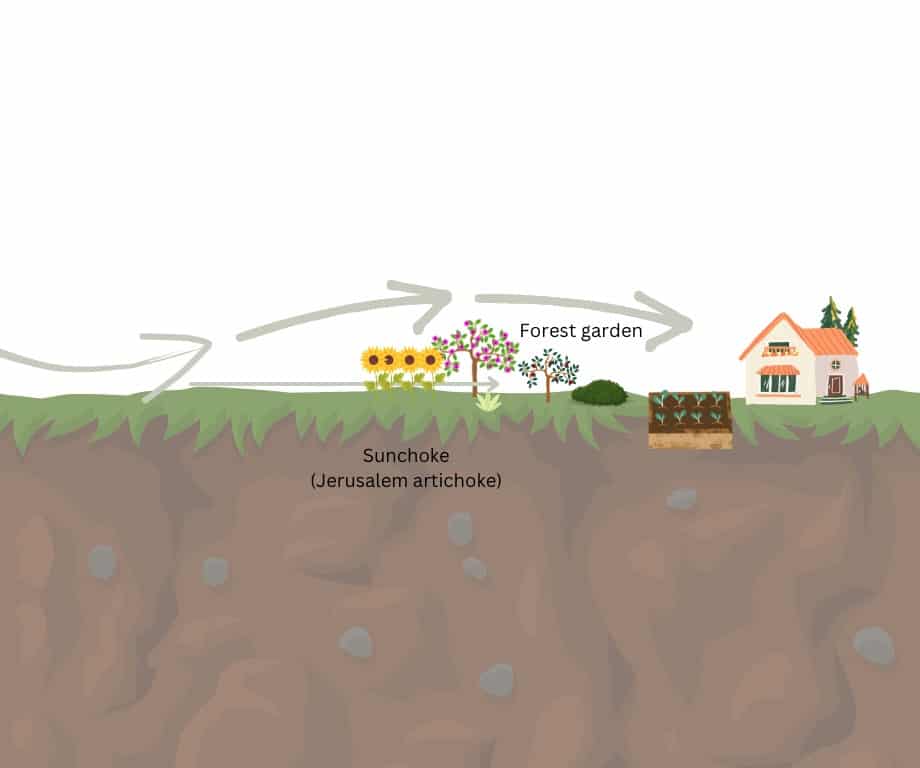

Example 5: A simple and cheap windbreak that also provides a food source

- Sunchokes grow in all zones! They are a healthy food to eat and grow prolifically fast. This can become invasive, so in addition to eating it, stomping portions of the plant down is recommended over time as well.

- The trunks of your forest garden are protected from the chilliest winds. The distance of coverage is not very far. Your fruit tree foliage will take on the highest winds if it is above the height of the leaning sunchokes. Sunchokes grow up to 10ft tall.

- No microclimate is created beyond what your forest garden does for itself. Your fruit trees would be serving as the protectors of the crops interplanted below.

This article was originally published on foodforestliving.com. If it is now published on any other site, it was done without permission from the copyright owner.

Recent Posts

There’s no shortage of full-sun ground covers for zone 4 climates! Each plant in this list can withstand the frigid temperatures and also enjoy the hot sun in summer. Full sun means that a plant...

There's no shortage of full sun ground covers, not even in zone 3! Zone 3 climates offer hot but short-lived summers and very cold winters. So each plant in this list can withstand the frigid...